Translated by Ann Goldstein

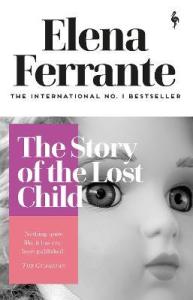

About the Book:

The Story of the Lost Child is the concluding volume in the dazzling saga of two women — the brilliant, bookish Elena, and the fiery, uncontainable Lila. Both are now adults, with husbands, lovers, aging parents, and children. Their friendship has been the gravitational center of their lives. Both women fought to escape the neighborhood in which they grew up — a prison of conformity, violence, and inviolable taboos. Elena married, moved to Florence, started a family, and published several well-received books. In this final novel she has returned to Naples, drawn back as if responding to the city’s obscure magnetism. Lila, on the other hand, could never free herself from the city of her birth. She has become a successful entrepreneur, but her success draws her into closer proximity with the nepotism, chauvinism, and criminal violence that infect the neighborhood. Proximity to the world she has always rejected only brings her role as its unacknowledged leader into relief. For Lila is unstoppable, unmanageable, unforgettable.

My Thoughts:

It’s taken me more than two years to read all four books in this series. The first two I read back-to-back, but I found the second one a pale cousin to its predecessor, so it was another year before I read the third book. Now, about eighteen months after the third, I have finally read the fourth and final book. My overall thoughts are that it was far too long, at least 100 pages too long, particularly in the first half with Elena and all of her self-indulgent waffling on about how unfair life is to her and how much she loves Nino, who, as I said from the outset, was not worth the effort! My contempt for Elena and Nino aside, from a political sociological viewpoint on Italy in the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s, it is brilliant. A stunning portrayal of a fractured nation grappling with democracy and dissent. And this is what I loved about the first and third books which has flowed through to this fourth one, that focus on the wider view of the nation and the effects of political dissent upon the different provinces and the way this shaped the people and guided their loyalties, not just to those leading, but to each other. The violence within Italy, written from a perspective of someone who has lived experience, was confronting.

‘Naples was the great European metropolis where faith in technology, in science, in economic development, in the kindness of nature, in history that leads of necessity to improvement, in democracy, was revealed, most clearly and far in advance, to be completely without foundation. To be born in that city – I went so far as to write once, thinking not of myself but of Lila’s pessimism – is useful for only one thing: to have always known, almost instinctively, what today, with endless fine distinctions, everyone is beginning to claim: that the dream of unlimited progress is in reality a nightmare of savagery and death.’

In terms of characters, I still don’t like Elena. If I’m going to be honest, I despise her. She is an incredibly arrogant and self-absorbed woman. Her adult relationship with Lina was interesting, I still felt that much of their friendship was one of convenience, left over from childhood and manifested in what they could do for each other, more than genuine affection. I felt a simmering of disgust at the way in which Elena was mining her old neighbourhood for literary gain.

‘The book was undoubtedly benefiting from everything that came from the neighbourhood. But the work proceeded so well mainly because I was attentive to Lila, who had remained completely within that environment. Her voice, her gaze, her gestures, her meanness and her generosity, her dialect were all intimately connected to our place of birth. Even Basic Sight, in spite of the exotic name (people called her office basissit), didn’t seem some sort of meteorite that had fallen from outer space but rather the unexpected product of poverty, violence, and blight. Thus, drawing on her to give truth to my story seemed indispensable. Afterward I would leave for good, I intended to move to Milan.’

Within this novel, the author explores the fragility of Lina’s mental state more thoroughly. I liked the way in which she wrote of the disconnection that Lila overwhelmingly felt.

‘But tonight I finally understood it: there is always a solvent that acts slowly, with a gentle heat, and undoes everything, even when there’s no earthquake. So please, if I insult you, if I say ugly things to you, stop up your ears, I don’t want to do it and yet I do. Please, please, don’t leave me, or I’ll fall in.’

On the topic of their friendship, I liked this perspective offered by Elena’s adult daughter:

‘When I complained of her coldness she said: It’s impossible to have a real relationship with you, the only things that count are work and Aunt Lina; there’s nothing that’s not swallowed up inside them, the real punishment, for Elsa, is to stay here.’

Despite the constant exasperation I felt about Elena and Lina and the way in which they would cyclically treat each other, the novel contains passages of such profound wisdom, in terms of the way in which Ferrante will break something down and examine it as if under a microscope. Take the deaths of the Solara brothers, as a case in point:

‘On the other hand I realized that I knew other things, things that no one knew and no one wrote, not even me. I knew that the Solaras had always seemed very handsome to us as girls, that went around the neighbourhood in their Fiat 1100 like ancient warriors in their chariots, that one night they had defended us in Piazza dei Martiri from the wealthy youths of Chiaia, that Marcello would have liked to marry Lila but then had married my sister Elisa, that Michele had understood the extraordinary qualities of my friend long before that and had loved her for years in a way so absolute that he had ended up losing himself. Just as I realized that I knew these things I discovered that they were important. They indicated how I and countless other respectable people all over Naples had been within the world of the Solaras, we had taken part in the opening of their businesses, had bought pastries at their bar, had celebrated their marriages, had bought their shoes, had been guests in their houses, had eaten at the same table, had directly or indirectly taken their money, had suffered their violence and pretended it was nothing. Marcello and Michele were, like it or not, part of us, just as Pasquale was. But while in relation to Pasquale, even with innumerable distinctions, a clear line of separation could immediately be drawn, the line of separation in relation to people like the Solaras had been and was, in Naples, in Italy, vague. The farther we jumped back in horror, the more certain it was that we were behind the line.’

So, after all this time and all those pages, would I recommend this series? Yes, go on, you know I do, even if it’s only for the sociology, politics, Italy, and the magnificent deconstruction of its characters. Ferrante writes with an honesty that is almost aggressive, it certainly makes you flinch with its intensity. Lila is a truly unforgettable character, Elena, the opposite. The rest of the expansive cast, with the exception of Nino, equally as unforgettable. I’ll give Ferrante kudos for making me despise two fictional characters with such ferocity.

‘There is this presumption, in those who feel destined for art and above all literature: we act as if we had received an investiture, but in fact no one has ever invested us with anything, it is we who have authorized ourselves to be authors and yet we are resentful if others say: This little thing you did doesn’t interest me, in fact it bores me, who gave you the right.’

Like pretty much everybody, I loved Ferrante when I first read her books, but I got tired of the whining and the self-absorption. It is, I think, important to read some books about this type of person so that you can improve your awareness of their issues, but enough can be enough.

The ones I had on the shelf, including this one, didn’t survive the last cull of my TBR. (Yes, I do cull, not much, but each year I set aside a ROTO pile (read Or Throw Out) and if I haven’t read them by the time the next cull is due, out they go.)

LikeLiked by 1 person

I have a bit of a cull system like that in place. Ferrante has a very set type that she writes about, that’s for sure. The Lying Life of Adults was similar to this series in tone, but not quite as bad. I have one more of hers on my shelf to see if she exclusively writes these sorts of characters or if she has ever written someone other.

LikeLike

The thing is, pretty much everyone I know has had the same gradual disenchantment with her, and I wonder why her editors haven’t intervened…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Maybe over in Italy they feel the opposite. And I do think her work is distinctly Italian, so perhaps it is just viewed as so realistic over there, lol.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m so glad you got around to finishing this one – I just recently did myself! Even though the quartet had ups and downs for me too (I’d imagine it does for every reader, they’re long volumes!), I’m still staggered by them as a feat, published in translation, under a pseudonym with the author remaining completely out of the public eye… I think I admire the spectacle as much as the work itself?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I agree. They’re definitely in a class of their own, for all of those reasons.

LikeLike

I just finished reading them in the original Italian. While they are not high art, I too believe they are important. They actually offered me insight into what it means to be female. Also, as many of us are more Lenu than we are Lila (petty, jealousy, diligent and getting ahead of our more inspired but less constant inspirations/muses), I totally appreciate and tolerate the character of lenu, and have learned much about myself from her.

LikeLiked by 1 person

These are definitely books that give so much to readers in terms of insight and introspection. I wonder if they were a different reading experience in their original Italian. People say that Allende is even better read in the original Spanish.

You make a good point here, about Lenu and human nature!

LikeLike